Hart County

Community Profile

Hart County is located in south-central Kentucky, within the Barren River Area Development District (BRADD). Formed in 1819 and named for Captain Nathaniel G. S. Hart, the county encompasses approximately 412 square miles of predominantly rural landscape. According to the 2020 U.S. Census, the county had a population of about 19,288 residents; recent estimates place it near 19,900. The county seat is Munfordville.

Hart County’s economy is shaped by agriculture and small business, with tourism playing a role as well—portions of Mammoth Cave National Park are located in the county, and cave systems (such as the Fisher Ridge Cave System) are present. The geography includes karst terrain, forested uplands, and both river and tributary systems.

The county is exposed to a wide range of natural and human-caused hazards common to south-central Kentucky, including flooding, severe storms, tornadoes, winter weather, drought, extreme temperatures, landslides (in certain terrain), hazardous materials incidents, sinkhole/karst issues, and emerging infectious disease events.

How Hazards are Examined

Each hazard in this multi-hazard multi-jurisdiction mitigation plan is examined through 6 specific lenses as required by FEMA. These include: the nature of the hazard, location, extent, historical occurrences, probability of future events, and impacts. Additionally, each participating jurisdiction reviews existing mitigation measures for each hazard, and creates additional mitigation actions to address any gaps.

Background:

A description of the hazard, including frequency, intensity, and duration

Location:

Geographic areas affected by the hazard; specific locations or features

Extent:

The severity or magnitude of the hazard

Past events:

Historical Occurrences involving the hazards

Probability of Future Events:

The likelihood of the hazard occurring in the future.

Impacts:

Potential consequences of the hazard both direct and indirect

Hazards in Hart County

Baseline Data

The following data points are used as baseline data to track trends across all 10 counties in the BRADD footprint. Data points are sourced from U.S. Census Bureau and 2019 American Community Survey 5-Year Estimates.

Dam Failure in Hart County

Dam Failure

Dam failure is the uncontrolled release of impounded water due to structural, mechanical, or hydraulic causes.

Types of Dams

There are two primary types of dams: embankment and concrete. Embankment dams are the most common and are constructed using either natural soil or rock or waste material from a mining or milling operation. They are often referred to as “earth-fill” or “rock-fill” based upon which of those two types of materials is used to compact the dam. Concrete dams are generally categorized as either gravity or buttress dams. Gravity dams rely on the mass of the concrete and friction to resist the water pressure. A buttress dam is a type of gravity dam where the large mass of concrete is reduced and the force of water pressure is “diverted to the dam foundation through vertical or sloping buttresses.”

The Energy and Environment Cabinet, authorized by KRS 151.293 Section 6 to inspect existing structures that meet the above definition of a dam, further notes three classifications of dams:

- High Hazard (C) – Structures located such that failure may cause loss of life or serious damage to houses, industrial or commercial buildings, important public utilities, main highways or major railroads.

- Moderate Hazard (B) – Structures located such that failure may cause significant damage to property and project operation, but loss of human life is not envisioned.

- Low Hazard (A) – Structures located such that failure would cause loss of the structure itself but little or no additional damage to other property.

High- and moderate-hazard dams are inspected every two years. Low-hazard dams are inspected every five years.

Quality of Dam Infrastructure

The American Society of Civil Engineers gave Kentucky a D+ on dam infrastructure, which is only slightly better than the national average. The average US dam is 60 years old, and most dams in Kentucky are over 50. As of 2019, 80 dams in the state are classified as two-fold risks, meaning that they are both high hazards and in poor or unsatisfactory condition. 47% of these 80 dams received that rating partially because they cannot hold enough rain during catastrophic storms. 89% of high hazard dams in Kentucky do not have complete emergency action plans on file with the state. 74% have simplified draft plans, but these are not widely shared and have not been adopted by local officials.

Types of Dam Failure

There are three types of Dam Failure:

- Structural: This common cause is responsible for nearly 30% of all dam failure in the United States. Structural failure of a dam occurs when there is a rupture in the dam or its foundation.

- Mechanical: Refers to the failure or malfunctioning of gates, conduits, or valves.

- Hydraulic: Occurs when the uncontrolled flow of water over the top, around, and adjacent to the dam erodes its foundation. Hydraulic failure is the cause of approximately 34% of all dam failures.

Extent

Dam failure in Hart County could result in localized to significant downstream flooding, depending on the size and location of the dam involved. The county contains a mix of small agricultural impoundments, private farm ponds, and several NRCS flood-control structures designed for stormwater management and erosion control. While these dams are relatively small compared to regional high-hazard dams, failure could still produce rapid downstream inundation, erosion of roadways, damage to culverts and bridges, and flooding of agricultural lands, homes, or outbuildings located in narrow valleys.

Because Hart County borders the Green River and relies on a network of tributaries—such as Lynn Camp Creek, Bacon Creek, and Cub Run—dam failure could exacerbate preexisting flood conditions, particularly during heavy rainfall. Failure of even a low-hazard dam during high-flow periods can increase inundation depth, accelerate flow velocity, transport debris, and temporarily alter stream channels. In steep or confined terrain, warning time would be extremely limited, making downstream areas particularly vulnerable.

History of Dam Failure

Hart County has no record of catastrophic dam failures, but the county has experienced dam-related issues consistent with rural Kentucky, including:

- Erosion, piping, and seepage at aging agricultural dams,

- Localized overtopping during high-intensity rain events,

- Maintenance deficiencies documented in periodic NRCS and Division of Water inspections, and

- Emergency drawdowns or repairs to alleviate pressure on small impoundments.

While these incidents have not resulted in major downstream flooding, they demonstrate the county’s vulnerability to structural deterioration, extreme precipitation, and limited maintenance resources.

Regional dam-failure events—such as impacts along the Green River basin in nearby counties, statewide overtopping incidents during the 2010 and 2021 flood years, and emergency actions taken at small farm ponds during heavy storms—provide relevant context for Hart County. These events show that prolonged rainfall, soil saturation, and undersized spillways are recurring stressors for older dams across the BRADD region.

Hart County’s risk is heightened by its concentration of small, privately owned dams, many of which were constructed decades ago and may not meet current design standards or inspection frequency. Because private dams fall outside routine oversight unless classified as high-hazard, their vulnerabilities may remain unnoticed until severe weather exposes structural weaknesses.

Probability

The probability of a dam failure in Hart County is considered low, but the potential consequences warrant continued monitoring and mitigation. Most dams within the county are small agricultural or private impoundments, which generally present a lower failure consequence but may have a higher likelihood of structural issues due to age, limited maintenance, and lack of formal inspection requirements. These smaller dams are more susceptible to problems such as seepage, erosion, spillway blockage, and overtopping during periods of intense rainfall.

Hart County does not contain large high-hazard dams, but the county’s hilly terrain, narrow valleys, and drainage characteristics mean that failure of even a small structure could result in rapid downstream flow with little warning. Climate trends indicating more frequent extreme precipitation events also increase stress on embankments and spillways, modestly raising the long-term likelihood of failure or overtopping.

Based on historical patterns in the region, continued aging of private dams, and projected increases in heavy rainfall, Hart County should plan for a low-probability but persistent risk, with the potential for occasional dam-related incidents or near-failures during severe storm seasons.

Impact

Built Environment:

A breach can produce rapid inundation that damages or destroys buildings, blocks roads with debris, disrupts traffic and emergency services, and threatens water/wastewater systems—especially if a reservoir supplies drinking water.

Natural Environment:

Floodwaves can scour channels, mobilize debris and contaminants, and disrupt aquatic habitats and riparian systems.

Social Environment:

Fast-arriving floodwaters elevate life-safety risk, particularly for people living/working in low-lying downstream areas with limited warning or evacuation options.

Climate Impacts on Dam Failure:

Increasingly intense rainfall, longer wet periods, and more frequent extreme storm events can raise hydraulic loading on dams, heighten the risk of overtopping, accelerate erosion of embankments and spillways, and reduce warning/response time. Climate-driven shifts can also stress aging infrastructure and complicate reservoir operations (e.g., balancing flood control with drought storage), making proactive maintenance, updated hydrologic/hydraulic studies, and EAP exercises even more critical.

Hart County’s vulnerability to dam failure is moderate, shaped by the county’s large number of small, privately owned agricultural dams and the prevalence of rural residences, farms, and local roadways located downstream of these structures. Many of the county’s dams were built decades ago and may not meet current engineering standards, especially if maintenance has been deferred or ownership has changed over time. Because most small dams are not classified as high-hazard, they are not subject to frequent regulatory inspection, which increases the likelihood that structural deterioration or spillway obstructions go undetected.

Downstream areas most at risk include narrow valleys, creek corridors, rural road crossings, and low-lying farmsteads, where even a limited breach could cause rapid flooding with little warning. Manufactured homes, older structures with low elevation, and homes located near small impoundments face elevated exposure. Roadway embankments, culverts, and small bridges are also vulnerable to washout during sudden releases of water.

Emergency-response challenges—such as the county’s rural topography, limited ingress and egress routes, and long travel distances between communities—increase the consequences of a failure event. Additionally, Hart County’s reliance on regional recreation, small businesses, and dispersed agricultural operations means that even localized damage can have broader community impacts.

Vulnerability centers on downstream settlements and critical routes that could be cut off. Even moderate failures can deposit debris that blocks access and delays emergency services. Adoption and exercising of EAP elements

with local responders can mitigate life-safety risks despite the low frequency of events.

Drought in Edmonson County

Description

Drought is a prolonged period of below-average precipitation that reduces soil moisture, surface water, and groundwater, stressing ecosystems, agriculture, and water supply systems. In Hart County, drought can be meteorological, agricultural, hydrological, or socioeconomic, with severity influenced by both climate conditions and community demand on limited water resources.

Types of Drought

The Palmer Drought Severity Index is the most widely used measurement of drought severity. The following indicators demonstrate drought severity by comparing the level of recorded precipitation against the average precipitation for a region.

- A meteorological drought is defined by the degree of dryness and the duration of a period without precipitation.

- Agricultural drought ties attributes of meteorological drought with agricultural impacts, often focusing on the amount of precipitation and evapotranspiration, which is the transference of water from the land to the atmosphere via evaporation. The magnitude of this type of drought is often conceptualized as the difference between plant water demand and available soil water. Because of this, the definition of agricultural drought accounts for the susceptibility of crops at the various stages of their development cycle

- Hydrological drought refers to below average water content in surface and subsurface water supply. This type of drought is generally out of phase with meteorological or agricultural drought.

- Socioeconomic drought focuses more on the social context that causes and intensifies drought conditions. This type of drought links meteorological, agricultural, and hydrological drought to supply and demand.

Location/Extent

Drought affects the entirety of Hart County, with especially significant consequences in rural agricultural areas that rely on dependable irrigation and livestock water. During extended dry periods, Barren River Lake levels can drop, affecting recreation and municipal supply. Historical droughts have driven soil-moisture deficits exceeding ~50% and reduced viability of staple crops such as corn and soybeans.

Sensitivity is elevated for row-crop and pasture lands, small public water systems or systems with leakage/limited storage, and surface-water/groundwater users lacking redundant sources. BRADD’s Water System Vulnerability to Drought resource further highlights system-level considerations for the region.

Past Events

Notable events include the 2012 drought, when much of Kentucky—including Hart County—reached D3 (Extreme Drought) on the U.S. Drought Monitor, with widespread agricultural losses, elevated fire risk, and water shortages. From 2000–2025, Hart County experienced ~53 weeks of D2 (Moderate) and ~8 weeks of D3 (Severe/Extreme) drought; USDA issued drought disaster declarations in 2022 and 2023 for documented production losses.

Probability

Long-term monitoring indicates drought is a recurrent hazard. Hart County experienced 597 total weeks of drought over the last 25 years—about a 46% chance that any given week features drought conditions. Projections suggest drought likelihood may increase with climate change as rising temperatures and shifting precipitation patterns extend dry periods.

Impact

Built Environment:

Lower reservoir and well levels can strain municipal water systems, increase infrastructure operating costs (e.g., pumping/energy), and trigger usage restrictions for businesses and institutions; prolonged deficits can reduce fire-flow availability for rural systems.

Natural Environment:

Drought reduces streamflow and aquatic habitat quality, stresses forests and grasslands, and can degrade water quality as lower volumes concentrate pollutants.

Social Environment:

The largest local effects are economic losses in agriculture (crop failures, livestock stress, higher irrigation costs) and secondary risks such as increased wildfire potential; households and small businesses can face water shortages and higher costs.

Climate Impacts on Dam Failure:

Rising temperatures increase evapotranspiration and soil‐moisture loss, while shifting precipitation patterns can produce longer dry spells punctuated by intense storms that do little to recharge groundwater. Hotter summers elevate water demand, stress crops and livestock, worsen algal blooms and other water-quality issues in low flows, and compound risks when heat waves coincide with drought—intensifying health, agricultural, and infrastructure impacts across Edmonson County.

Drought Vulnerability in the BRADD Region

Soil Susceptibility

Soil’s susceptibility to drought varies due to a myriad of factors. The map below depicts vulnerability to drought based on soil type from a moisture retention and availability perspective. For example a shallow fragipan limits the depth of the soil making it more vulnerable to moisture loss. Grey areas indicate that no soil data was available due to lakes, heavily urbanized areas, or strip mining. Susceptibility to Drought Scores were established using the criteria of infiltration, water movement, and water supply for the soils defined in the NRCS Soil Surveys that encompass the state.

Hart County’s drought vulnerability is moderate to low, shaped by its rural character, widespread private wells, and reliance on pasture-based and small-scale agricultural operations. Older adults and medically vulnerable residents face elevated heat risk during drought periods. Agricultural producers—particularly livestock and hay operations—are highly susceptible to economic losses during extended dry spells. Rural water associations and households using private wells may face capacity limitations or costly maintenance during prolonged drought. Limited redundancy in some rural water systems and the county’s dispersed population increase response challenges during severe drought events.

Hart County’s public water system demonstrates low to moderate vulnerability to drought.

The soil susceptibility map indicates that large swaths of Hart County’s soil experience moderately high susceptibility to drought.

Overall, Hart County has a moderately high vulnerability to drought. Because drought is a non-spatial hazard, this same analysis can be applied to its respective cities – Bonnieville, Horse Cave, and Munfordville.

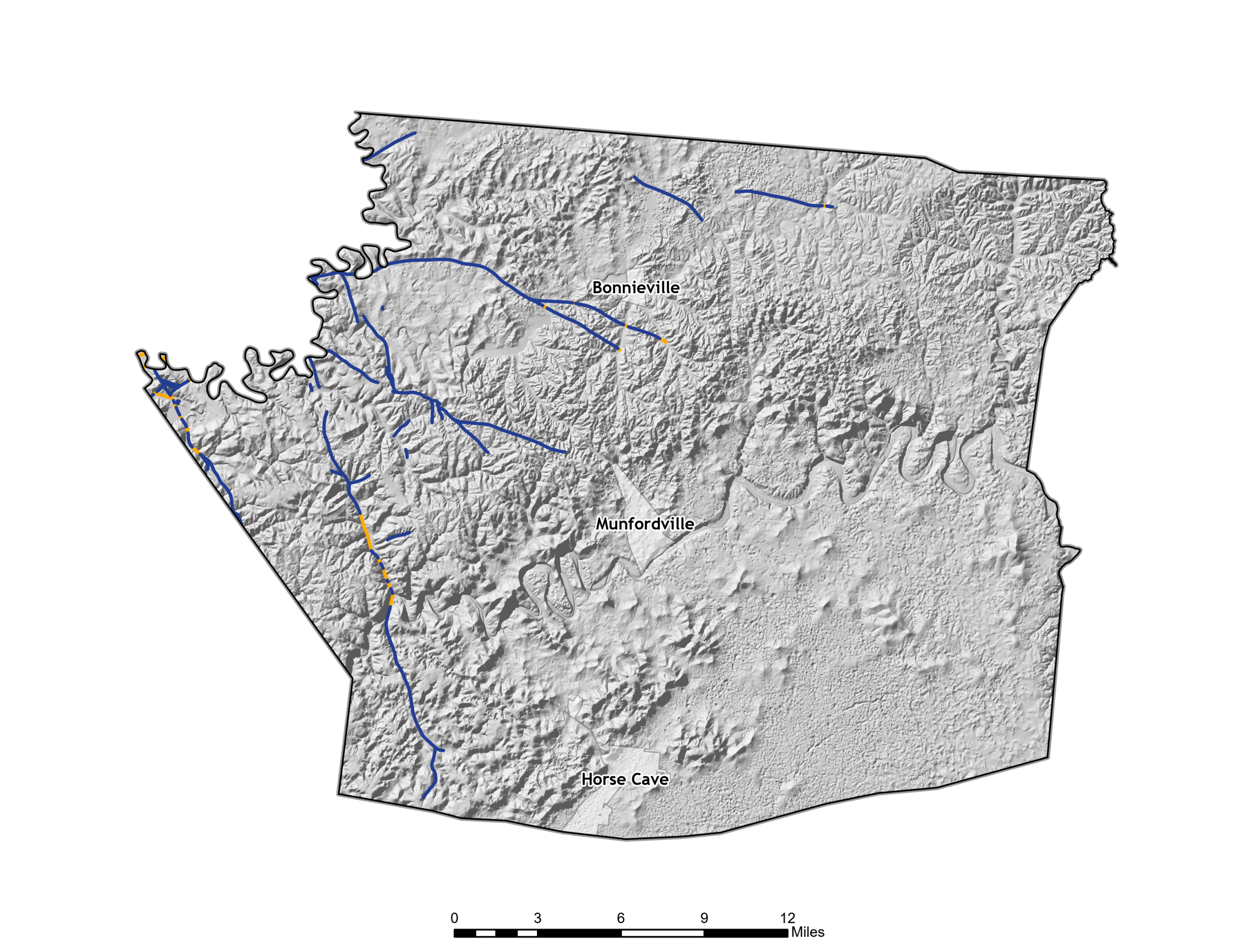

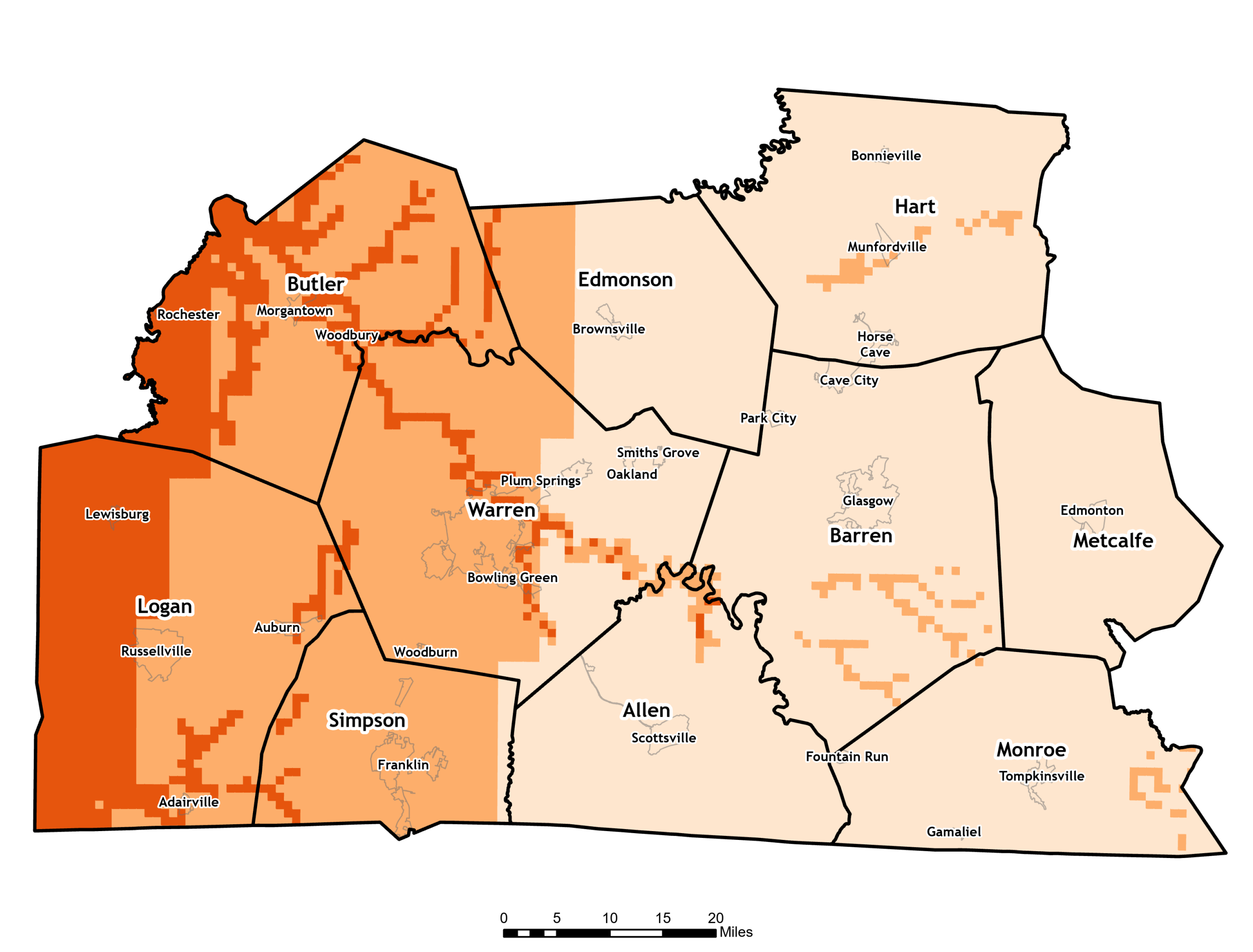

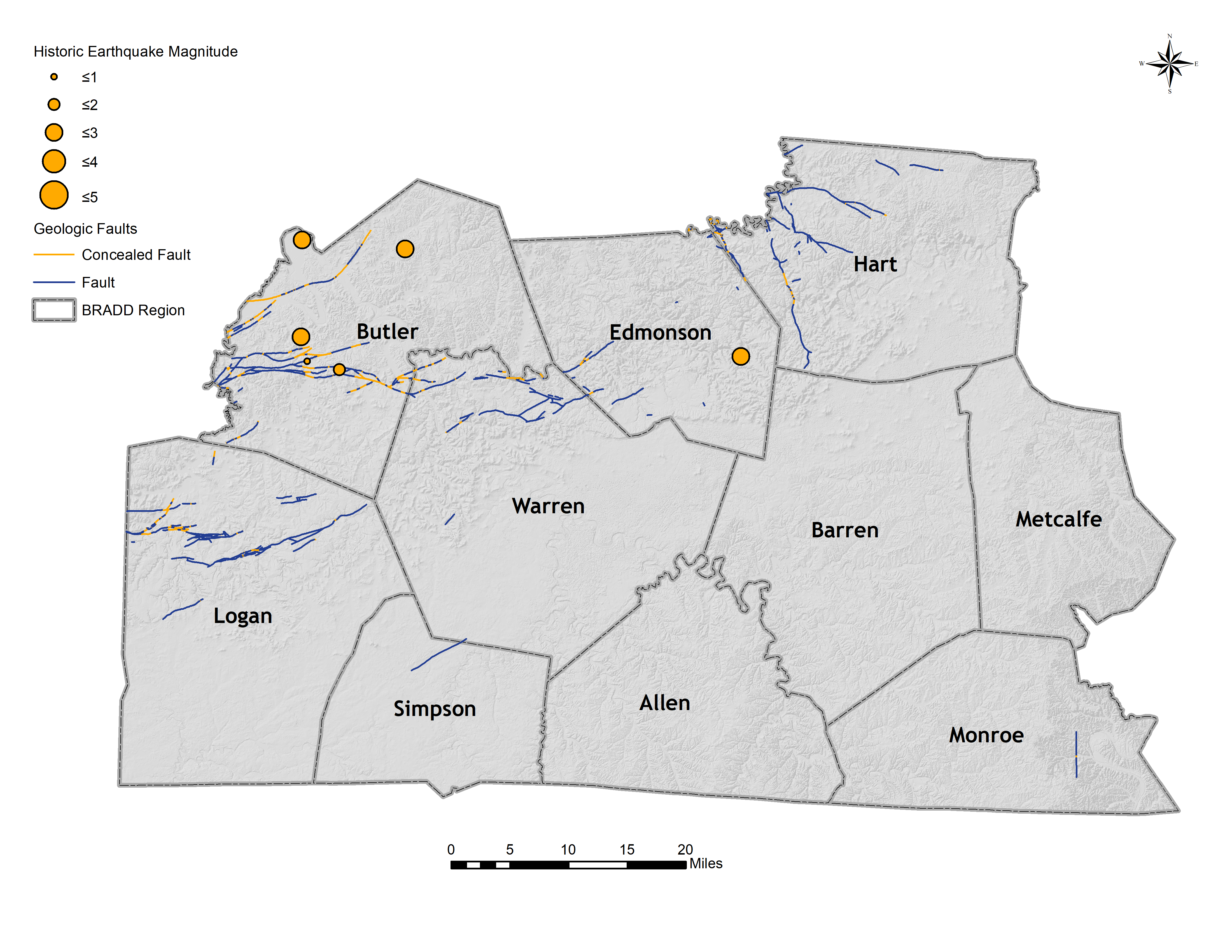

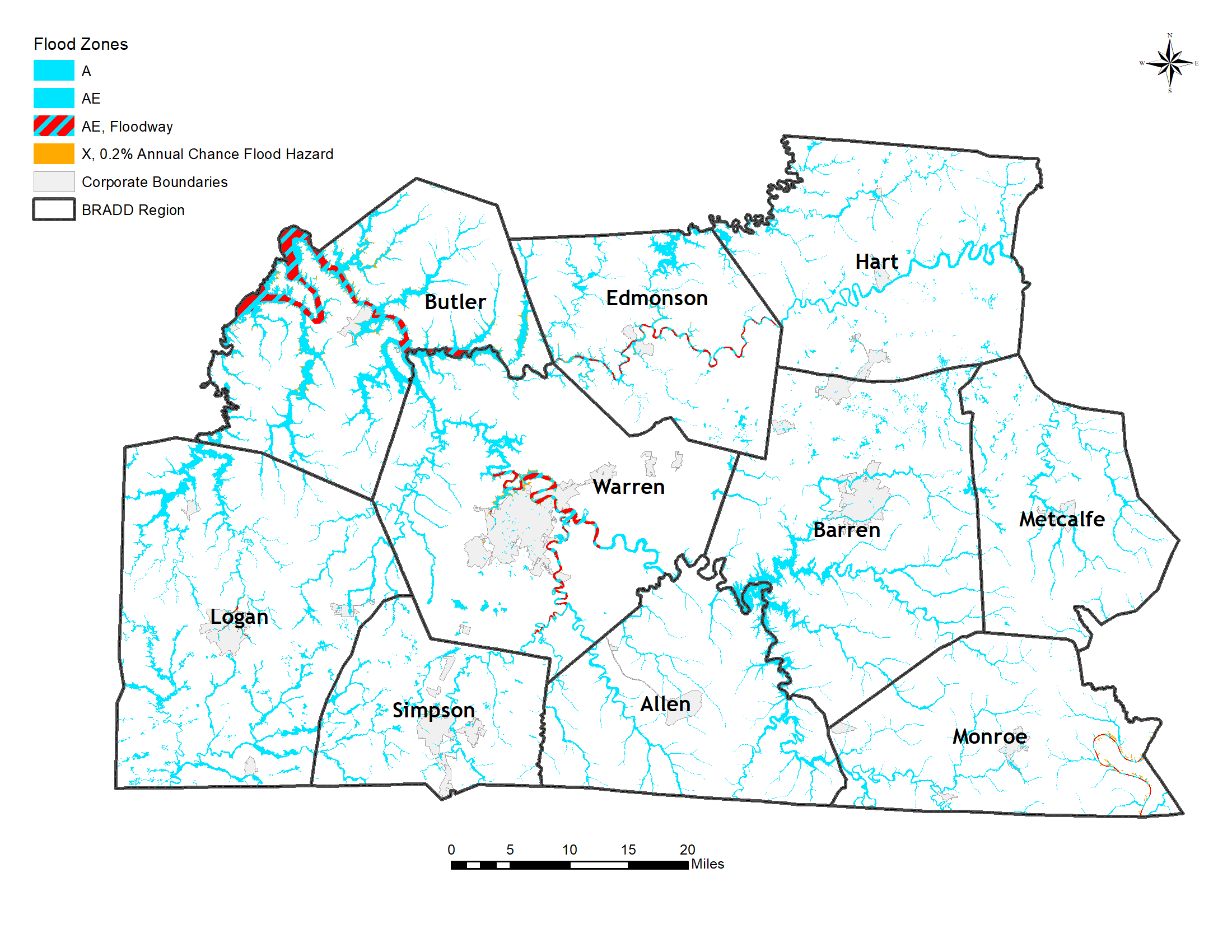

Earthquakes in Hart County

Description

An earthquake is a sudden release of energy in the Earth’s crust that produces ground shaking capable of damaging buildings, lifelines, and critical services. In south-central Kentucky, risk is influenced by regional seismic zones (notably New Madrid and Wabash Valley) and by local site conditions that can amplify shaking—especially softer soils over bedrock and saturated valley deposits. Building code provisions and seismic design values are informed by the USGS National Seismic Hazard Model.

Location/Extent

Kentucky is affected by nearby seismic zones—New Madrid (most active east of the Rockies) and Wabash Valley (capable of M5.5–6.0 damage near population centers). Potential shaking in Butler County ranges from weak/noticeable (MMI II–IV) during distant events to light–moderate (MMI V–VI) in rarer, larger scenarios; secondary effects can include nonstructural damage, minor slope instability, and utility disruptions. The eastern U.S. crust transmits shaking efficiently, so distant earthquakes can be widely felt.

Severity is commonly expressed by earthquake magnitude and by shaking intensity (Modified Mercalli Scale). Butler County’s worst-case consequences depend on regional event size/distance and local amplification/liquefaction potential.

| Intensity | Verbal Description | Witness Observation | Maximum Acceleration (cm/sec2) | Corresponding Richter Scale |

| I | Instrumental | Detectable on Seismographs | <1 | <3.5 |

| II | Feeble | Felt by Some People | <2.5 | 3.5 |

| III | Slight | Felt by Some People Resting | <5 | 4.2 |

| IV | Moderate | Felt by People Walking | <10 | 4.5 |

| V | Slightly Strong | Sleepers Awake; Church Bells Ringing | <25 | <4.8 |

| VI | Strong | Trees Sway; Suspended Objects Swing; Objects Fall off Shelves | <50 | 4.8 |

| VII | Very Strong | Mild Alarm; Walls Crack; Plaster Falls | <100 | 6.1 |

| VIII | Destructive | Moving Cars Uncontrollable; Masonry Fractures; Poorly Constructed Buildings Damaged | <250 | |

| IX | Runious | Some Houses Collapse; Ground Cracks; Pipes Break Open | <500 | 6.9 |

| X | Disastrous | Ground Cracks Profusely; Many Buildings Destroyed; Liquefaction and Landslides Widespread | <750 | 7.3 |

| XI | Very Disastrous | Most Buildings and Bridges Collapse; Roads, Railways, Pipes, and Cables Destroyed; General Triggering of Other Hazards | <980 | 8.1 |

Past Events

Hart County has experienced no recorded damaging earthquakes ≥M3 within its boundaries, but residents have periodically felt mild shaking from events originating in nearby seismic zones. Small earthquakes associated with the East Tennessee Seismic Zone (ETSZ) and Wabash Valley Seismic Zone (WVSZ) have produced weak, widely felt tremors across south-central Kentucky, occasionally reported by residents in Hart, Edmonson, Green, and Barren Counties.

Regionally, the New Madrid Seismic Zone (NMSZ) remains the most significant historical influence. The 1811–1812 New Madrid earthquakes generated strong shaking across Kentucky, including the area that would become Hart County, though no detailed local accounts exist due to sparse settlement at the time. More recent moderate regional events—such as earthquakes in central Tennessee (M4.4 in 2017), western Kentucky and southern Illinois, and small ETSZ events during the 2010s—were felt across the BRADD region due to the efficient transmission of seismic waves through eastern U.S. bedrock.

Although Hart County has not experienced structural damage from past earthquakes, the consistent pattern of regionally felt events reinforces the county’s exposure to low-probability but potentially high-consequence seismic hazards linked to the larger NMSZ, WVSZ, and ETSZ systems.

Probability

The probability of a damaging earthquake in Hart County is considered low, but the probability of felt seismic activity is moderate due to the county’s proximity to three major regional seismic zones: the New Madrid Seismic Zone (NMSZ) to the west, the Wabash Valley Seismic Zone (WVSZ) to the northwest, and the East Tennessee Seismic Zone (ETSZ) to the southeast. Small, weak earthquakes originating in these zones occur regularly and may be felt in Hart County every few years, typically producing MMI II–IV shaking.

Moderate shaking (MMI V–VI) is possible within a 50-year planning horizon, primarily from events in the ETSZ or WVSZ. A large New Madrid earthquake—while a low-probability, high-consequence event—could produce widespread impacts across the region, including Hart County, despite the distance from the epicenter.

Climate change does not influence earthquake probability, but increasing rainfall variability and flood-soil saturation may indirectly affect slope stability or soil response during shaking. Overall, Hart County should plan for occasional felt events and maintain readiness for rare but potentially consequential regional earthquakes.

Impact

An earthquake could result in structural damage to older buildings, critical facilities, and infrastructure not designed to modern seismic codes. Bridges, utilities, and water systems could sustain significant damage, leading to service disruptions. Secondary impacts might include landslides in certain areas, hazardous material spills, and challenges in emergency response due to blocked roads and damaged communication systems. Economic losses could be substantial, particularly for uninsured property owners.

Built Environment:

Shaking can damage homes and business structures, collapse unreinforced elements, and disrupt roads/bridges, power, water/wastewater, and telecom. Post-event debris and utility outages can hinder emergency response.

Natural Environment:

Secondary effects—liquefaction, landslides, fires, and hazmat releases—can degrade soils, waterways, and habitats.

Social Environment:

Transportation disruption, hospital surge, power/water interruptions, and communications overload elevate life-safety risk and complicate reunification and care for vulnerable groups (children, older adults, LEP populations).

Climate Impacts on Earthquakes:

While climate change does not drive tectonic earthquakes, hydrologic extremes (prolonged drought, heavy precipitation, groundwater withdrawal/recharge) may alter subsurface stresses in limited contexts. The BRADD region has an overall low earthquake risk, so any climate influence on local frequency/severity is likely minor relative to tectonic controls.

Earthquake Vulnerability in Allen County

Butler County is mapped in a “high perceived shaking” zone for high-magnitude regional scenarios and contains significant local fault lines. Because earthquakes are non-spatial at the county scale, this vulnerability characterization applies countywide (including Morgantown, Rochester, and Woodbury). Key sensitivity factors remain older/unnretrofitted buildings, critical facilities, bridges, and lifelines on softer soils or in potential liquefaction areas.

Hart County’s vulnerability to earthquakes is low to moderate, shaped by its rural building stock, presence of older homes, and limited seismic design in structures built prior to modern building codes. Unreinforced masonry buildings, older brick structures in small communities, and long-span roofs (gyms, warehouses, barns) are particularly susceptible to shaking-related damage. Manufactured housing, while lighter in weight, may shift or sustain anchoring failures during moderate ground motion.

Critical facilities constructed before current seismic standards—such as schools, first-response buildings, and water/wastewater infrastructure—may experience nonstructural failures (ceiling collapses, broken piping, equipment damage) even during lower-intensity shaking. Underground utilities may also be vulnerable to joint separation or service disruption.

Populations most vulnerable include older adults, residents in older or poorly anchored structures, and households with limited resources for retrofitting or repairs. Rural road networks, located in karst terrain and along creek valleys, may experience localized slope instability or shoulder failures that complicate emergency response. While catastrophic impacts are unlikely, even moderate earthquakes could produce disruptive, system-wide effects due to the county’s reliance on regional healthcare, utilities, and emergency-services support.

Hart County is within the “light” perceived shaking zone for a high magnitude earthquake and does not contain significant fault lines.

Because of these factors, Hart County experiences low vulnerability to earthquakes. Because earthquakes are non-spatial hazards, it can be assumed that this analysis should be applied to Hart County’s respective cities – Bonnieville, Horse Cave, and Munfordville.

Extreme Temperatures in Hart County

Description

“Extreme temperature” includes both extreme heat (multi-day heat waves driven by high temperature and humidity) and extreme cold (cold waves with dangerous wind chills). The National Weather Service (NWS Louisville/LMK) issues Heat Advisories when Heat Index values are around 105°F for ≥2 hours and Excessive Heat Warnings at ≥110°F (or prolonged 105–110°F). LMK’s cold guidance treats apparent temperatures ≤ −10°F in south-central Kentucky as Extreme Cold thresholds for watch/warning products. These index-based triggers better capture human health risk than air temperature alone.

Location/Extent

Location and Extent

Extreme temperature hazards in Hart County include both excessive heat and extreme cold. These conditions can affect the entire county, though the severity of impacts varies by housing quality, access to heating and cooling, and resident vulnerability.

Excessive heat typically occurs during late summer, when high temperatures combine with elevated humidity to produce heat index values exceeding 100–105°F. These events strain home cooling systems, increase energy demand, and pose severe health risks for older adults, outdoor workers, young children, and households without adequate air conditioning. Manufactured homes and older structures with limited insulation face the highest levels of interior heat buildup.

Extreme cold and dangerous wind chills occur most often from December through February. Low temperatures can freeze pipes, strain electric heating systems, and stress private well infrastructure. Rural homes—particularly those in exposed areas or with aging insulation—face increased vulnerability during cold snaps. Ice accumulation from winter precipitation can exacerbate cold-related challenges by damaging power lines and prolonging outages.

Both heat and cold events can be intensified by Hart County’s rural nature, limited access to cooling/warming centers, and the distance some residents must travel to reach services during hazardous conditions.

Historical Occurrences

Cold. Within the regional record (2010–2021), Hart County had one wind chill watch (2014) and one wind chill warning (2015); these events were issued region-wide.

Heat. Across 2010–2021, the BRADD region recorded 18 excessive heat watches and 71 excessive heat warnings; county-level breakdowns show Hart County averaged ~27.7 extreme-heat days per year (2010–2016).

Probability

Expect recurrent heat seasons with periodic advisory/warning episodes and less frequent but hazardous cold outbreaks. While year-to-year frequency varies, local planning should assume annual heat advisories are likely, with occasional excessive-heat warnings, and intermittent extreme-cold events in some winters.

Impact

Extreme heat can lead to heat exhaustion and heatstroke, particularly in outdoor workers, the elderly, and low-income households without access to cooling. It also increases energy demand, raising utility costs and the likelihood of power outages. Severe cold poses risks of frostbite, hypothermia, and infrastructure damage, including frozen pipes and malfunctioning heating systems. Both extremes can disrupt agricultural yields, livestock health, and local economies.

Built Environment:

Cold can burst buried water pipes, strain metal bridge members, and affect trucking/rail operations (e.g., diesel gelling). Heat can soften asphalt, stress vehicle cooling systems and rail operations, and increase water demand, sometimes reducing fire-flow availability.

Natural Environment:

Cold snaps threaten livestock and wildlife and can freeze ponds/streams. Heat can degrade water quality, drive algal blooms, and reduce crop yields and dairy productivity.

Social Environment:

Cold elevates exposure risks for people without adequate shelter or heat and can increase CO poisoning and fire risk; both cold and heat create economic losses (e.g., utility repair, agriculture) and can trigger business/school closures. Heat is the leading U.S. weather-related killer, with illnesses from fatigue to heat stroke.

Climate Impacts on Extreme Temperatures:

Climate change models predict and increase in overall temperature globally for the coming decades, including the BRADD region. With a potential rise of several degrees Fahrenheit, multiple services, systems, and activities face disruption and impact. Temperature increases this small may not seem threatening, but the cumulative impacts will affect weather events, human health, and ecosystem functions, along with economic and social issues related to energy use and cost of living.

Working with

AT&T’s Climate Resilient Communities Program and the

Climate Risk and Resilience (ClimRR) Portal, BRADD identified additional opportunities for hazard mitigation action items associated with climate impacts for Extreme Temperatures in the Barren River Region. To view an interactive report of these findings,

click here.

Hart County’s vulnerability to extreme temperatures is moderate to high, shaped by its rural housing stock, high proportion of manufactured homes, and dependence on electric or propane heating and cooling systems. Many older homes lack adequate insulation or weatherization, increasing indoor heat buildup during summer and heightening the risk of frozen pipes or heating failures during winter cold snaps. Households relying on private wells are particularly vulnerable during prolonged cold, as frozen pumps or loss of power can disrupt water access.

Populations at greatest risk during extreme heat include older adults, young children, outdoor laborers, and residents without reliable air conditioning or the financial means to manage high electricity costs. During extreme cold, low-income households, those using space heaters or outdated HVAC systems, and individuals with limited ability to travel to warming centers face elevated exposure. Rural isolation, long emergency response times, and inconsistent broadband coverage further complicate outreach and assistance during severe temperature events.

Essential facilities such as schools, long-term care homes, and EMS also face operational strain during prolonged heat or cold, especially when staff, equipment, or energy supply systems are stressed. Supply-chain disruptions, increased utility demand, and potential power outages add to the county’s vulnerability, as many rural areas lack redundancy in electrical infrastructure.

Since 2010, Hart County experienced one wind chill watch (2014) and one wind chill warning (2015).

At a county scale, extreme temperatures are non-spatial, so exposure is countywide. Hart County’s extreme cold vulnerability is rated moderate overall (with Munfordville noted as high) based on past watches/warnings and sensitivity to power-outage cold snaps.

For extreme heat, Hart shows moderate vulnerability, reflecting its ~28 heat-days/year baseline and sensitivity in smaller urban areas to urban heat island effects.

Unless otherwise noted, Bonnieville, Horse Cave, and Munfordville reflect Hart County’s overall history of extreme temperature, and therefore experience moderate vulnerability as well.

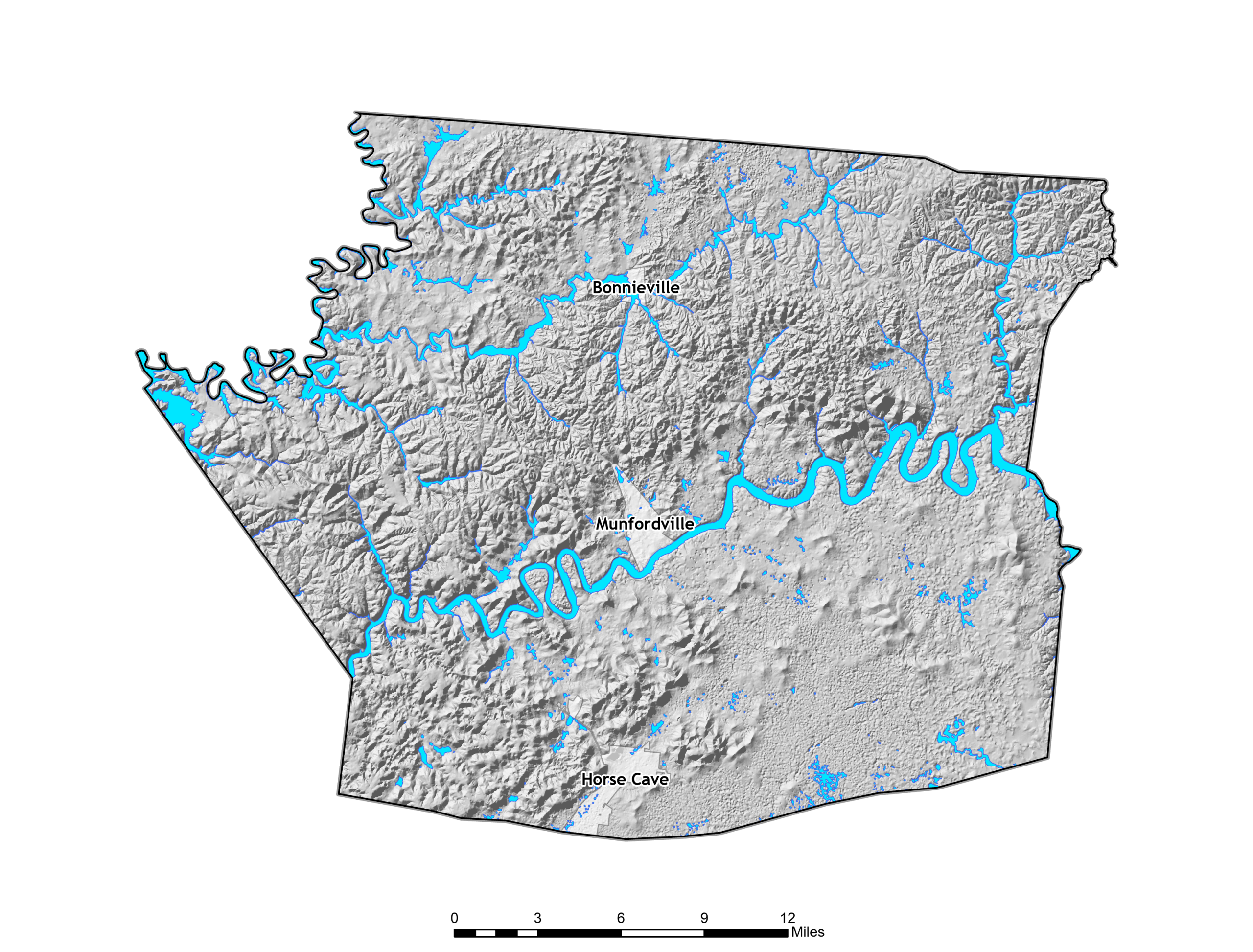

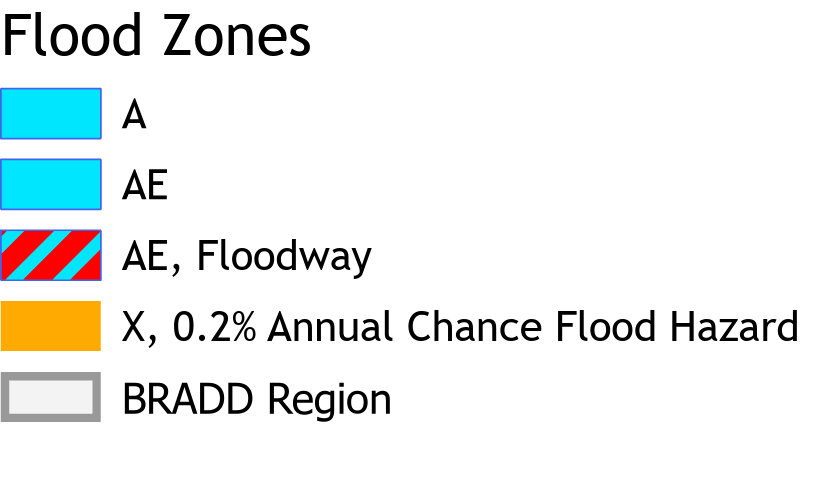

Flooding in Hart County

Description

Flooding is the overflow of water onto land that is normally dry, driven in south-central Kentucky by prolonged or intense rainfall, saturated soils, snowmelt, or infrastructure/ground-failure conditions. In addition to river (out-of-bank) flooding, the county can experience flash flooding in small basins and urbanized areas, urban/poor-drainage flooding from impervious cover, and ground-failure/karst-related flooding where subsidence or clogged sinkholes impede drainage. These events are increasing in frequency and severity due to regional climate trends, which elevate the risk for both urban and rural communities. (See BRADD’s work with AT&T’s Climate Resilient Communities Program and the Climate Risk and Resilience (ClimRR) Portal for a more in-depth look at how flooding is expected to be impacted by climate change throughout the region.)

Location and Extent

Flooding in Hart County includes riverine flooding, flash flooding, and localized or poor-drainage flooding, with impacts shaped by the county’s mix of river valleys, steep headwater basins, and extensive karst features. The Green River, Nolin River, and numerous tributaries—including Bacon Creek, Lynn Camp Creek, Bear Creek, and Lick Creek—can rise rapidly during heavy rainfall, inundating low-lying roads, agricultural areas, and river-adjacent neighborhoods. Riverine flooding is most prominent near Munfordville, Bonnieville, Horse Cave, and rural stretches along the Green River corridor.

Flash flooding occurs frequently in narrow hollows, steep terrain, and roadway low-water crossings, where intense rainfall can quickly overtop roadways, wash out culverts, and cause bank erosion. Areas with undersized drainage systems—particularly in older developed areas—experience recurring issues during high-intensity storms.

Hart County’s widespread karst landscape introduces additional flood dynamics. Sinkholes, closed depressions, and losing streams can capture stormwater when inlets clog or soils become saturated, resulting in sudden, localized flooding even outside mapped Special Flood Hazard Areas (SFHAs). Agricultural lands and rural roads overlying sinkhole plains often experience recurring ponding and drainage problems.

Flooding affects the entire county, but the most severe impacts occur along river corridors, in steep or confined drainage basins, and at numerous low-water crossings typical of rural Hart County.

Repetitive-Loss & Severe Repetitive-Loss Properties

Hart County has very few repetitive-loss (RL) or severe repetitive-loss (SRL) properties under FEMA’s definitions. The unincorporated county, as well as the Cities of Bonnieville and Horse Cave, each have zero RL or SRL properties under both the National Flood Insurance Program (NFIP) and Flood Mitigation Assistance (FMA) criteria.

The City of Munfordville, however, has one (1) property with RL/SRL history. This structure is a single-family residence. Under FEMA classifications, this property is not considered an NFIP Repetitive-Loss or NFIP Severe Repetitive-Loss property. However, under the FMA definitions, it qualifies as both a Repetitive-Loss (RL) and Severe Repetitive-Loss (SRL) property. There are no 2–4 family occupancy properties or non-residential properties in Munfordville that meet RL or SRL criteria under either definition.

This pattern indicates that although Hart County experiences widespread flood exposure, the overall number of repetitive-loss structures is extremely low, reflecting its rural development profile and the limited concentration of flood-prone residential clusters.

Historical Occurances

Hart County experienced 39 flood events over 20 years (~2 events/year). This places Hart County in the upper-range of regional flood frequency.

Exposure in Hart County is countywide, with riverine flooding along the Green River, Nolin River, and their associated tributaries; flash flooding in steep headwater basins, narrow hollows, and at rural low-water crossings; and localized or poor-drainage flooding within the Cities of Munfordville, Bonnieville, Horse Cave, and other small communities. Low-lying recreation areas, agricultural lands, and river-adjacent facilities also experience periodic inundation during high-water events. Hart County’s extensive karst terrain—particularly in areas surrounding Horse Cave, Cave City, and broad sinkhole plains—can concentrate stormwater, leading to sudden, localized flooding when sinkhole inlets clog, depressions fill, or soils become saturated.

Click Here to view a summary of all past Disaster Declarations in the BRADD Region.

Below you will find a listing of past NOAA Flood and Flash-Flood Events from 2000-2020 for Hart County.

Hart County Flood Events

| EVENT_ID | CZ_NAME_STR | BEGIN_LOCATION | BEGIN_DATE | BEGIN_TIME | EVENT_TYPE | DEATHS_DIRECT | INJURIES_DIRECT | DAMAGE_PROPERTY_NUM | DAMAGE_CROPS_NUM | EVENT_NARRATIVE | EPISODE_NARRATIVE |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EVENT_ID | CZ_NAME_STR | BEGIN_LOCATION | BEGIN_DATE | BEGIN_TIME | EVENT_TYPE | DEATHS_DIRECT | INJURIES_DIRECT | DAMAGE_PROPERTY_NUM | DAMAGE_CROPS_NUM | EVENT_NARRATIVE | EPISODE_NARRATIVE |

| 5,596,583 | HART (ZONE) | 03/01/1997 | 1,500 | Flood | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Widespread flooding and/or flash flooding occurred as a result of 4 to 8 inches of rainfall in less than 24 hours. Numerous roads were water covered and closed across these counties and many homes and businesses were effected. All of these counties were declared federal disaster areas eligible for financial aid. Damage estimates include flash flooding from early March 1 through early March 2. | ||

| 5,596,822 | HART (ZONE) | 03/01/1997 | 1,800 | Flood | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 to 9 inches of rain fell in less than 24 hours causing widespread flooding and/or flash flooding resulting in numerous water covered and closed roads, evacuations and rescues. Most of these counties were declared disaster areas and given federal assistance. The exceptions were Clinton, Cumberland, Garrard, Green, Lincoln, Madison and Marion. Many homes and businesses were effected during the flooding and flash flooding. Damage amounts include flooding and flash flooding totals over the 2 day period. | ||

| 5,597,013 | HART CO. | COUNTYWIDE | 03/01/1997 | 2,100 | Flash Flood | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Over 2 inches of rain fell on top of 24 hour totals from 4 to 8 inches which resulted in widespread flash flooding with many roads water covered and closed. | |

| 5,596,801 | HART (ZONE) | 03/02/1997 | 400 | Flood | 0 | 0 | 1,000,000 | 0 | The Green River crested at 30.7 feet at Rochester at 1000 am est on March 7 (flood stage is 17 feet). This is the second biggest flood next to January 1950. Many homes were flooded out in Rochester and Woodberry along the river. In Woodberry, the river crested at 48.9 feet (flood stage is 33 feet) at 11 am est March 5. At Brownsville, the river crested at 33.8 feet (flood stage is 18 feet) at 4 pm est on March 5. This caused mainly bottomland flooding. At Munfordville, the river crested at 43.9 feet at 10 pm est March 3 (flood stage is 28 feet). This caused significant bottomland flooding. 25 families were cut off by the water there. These three counties received federal disaster aid. | ||

| 5,597,037 | HART CO. | COUNTYWIDE | 03/05/1997 | 1,230 | Flash Flood | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 to 3 inches of rain fell on top of already saturated grounds leading to widespread flash flooding with many roads water covered. | |

| 5,597,245 | HART (ZONE) | 03/20/1997 | 100 | Flood | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | The Green River at Munfordville crested at 28.6 feet (flood stage is 28 feet) at 3 am est on March 20 producing minor flooding. | ||

| 5,627,741 | HART (ZONE) | 01/08/1998 | 1,900 | Flood | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | The Rolling Fork of the Salt River at Boston crested at 36.4 feet (flood stage is 35 feet) at 4 pm est January 10. Some minor agricultural bottom flooding resulted. The Green River at Munfordville crested at 28.9 feet (flood stage is 28 feet) at 11 pm est on January 8. A city park was flooded. Minor cropland flooding resulted along the Licking River at Blue Licks Spring as the river crested at 26.5 feet (flood stage is 25 feet) at 11 pm est January 8. Finally, Stoner Creek at Paris crested at 19 feet (flood stage is 18 feet) at 3 am est on January 8. Only minor flooding resulted. | ||

| 5,639,032 | HART (ZONE) | 04/17/1998 | 1,800 | Flood | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Significant rainfall caused flooding along the Green, Rough and Ohio Rivers and the Rolling Fork of the Salt River. Minor flooding occured along low-lying county roads and agricultural bottomland. The following are crests and dates: Rolling Fork of the Salt River at Boston: 36.7 feet (flood stage is 35 feet) at 0900 am est on April 18; Dundee along the Rough River: 25.4 feet (flood stage is 25 feet) at 100 pm est on April 17; Munfordville along the Green River: 28.2 feet (flood stage is 28 feet) at 4 pm est on April April 17; Brownsville along the Green River: 19.7 feet (flood stage is 18 feet) at 3 pm est on April 18; Woodbury along the Green River: 36.5 feet (flood stage is 33 feet) at 130 pm est on April 19; Rochester Ferry along the Green River: 19.6 feet (flood sstage is 17 feet) at 1 pm est on April 20; Tell City along the Ohio River: 39.4 feet (flood stage is 38 feet) at 4 pm est on April 25. | ||

| 5,249,990 | HART CO. | HORSE CAVE | 06/04/2001 | 626 | Flash Flood | 0 | 0 | 12,000 | 0 | Highway 218 was closed due to high water. Three cars had to be pulled from a low lying portion of Highway 218. | |

| 5,285,977 | HART CO. | COUNTYWIDE | 03/20/2002 | 1,000 | Flash Flood | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Several roadways were closed by high water. | |

| 5,286,113 | HART (ZONE) | 03/21/2002 | 1,000 | Flood | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||

| 5,343,101 | HART (ZONE) | 02/16/2003 | 1,430 | Flood | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||

| 5,386,589 | HART (ZONE) | 02/06/2004 | 2,235 | Flood | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |||

| 5,446,892 | HART CO. | SOUTH PORTION | 05/20/2005 | 10 | Flash Flood | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Roadways were flooded in the Munfordville and Horse Cave areas. Two to four feet of water covered a four mile stretch of Highway 218 near Horse Cave. | Thunderstorms ahead of an advancing cold front caused wind damage over much of Central Kentucky, mostly in the form of downed trees and power lines. There were also widespread reports of large hail, and a few more reports of non-severe hail in other locations. Flooding of low-lying areas, and streams flowing out of banks, also resulted from the thunderstorms. |

| 5,520,658 | HART CO. | LINWOOD | 08/10/2006 | 1,738 | Flash Flood | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Water covered Power Mills Road, or State Highway 569. | |

| 71,909 | HART CO. | HORSE CAVE | 01/10/2008 | 1,500 | Flash Flood | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Highway 218 was closed for a half hour by high water. | A warm front acted as a focus for some heavy rains over parts of central Kentucky. Along with this, an upper level system set off some severe thunderstorms. |

| 80,761 | HART CO. | LOGSDON VLY | 02/07/2008 | 830 | Flood | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | The Green River at Munfordville crested at 28.5 feet around 4 PM EST on February 7. Flood stage at Munfordville is 28 feet. Minor flooding occurs at this level, with flooding at the city park under the U.S. 31W bridge. | Heavy rains on the night of February 5th to 6th caused minor flooding on many area rivers and streams. |

| 98,468 | HART CO. | MUNFORDVILLE | 04/04/2008 | 2,110 | Flood | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | The Green River at Munfordville crested at 30.5 feet around 1245 PM CST on April 5. Flood stage at the site is 28 feet. Minor flooding occurs at this level, with the city park flooded under the U.S. Highway 31W bridge. | A frontal system and upper level low brought widespread heavy rains and flooding to central Kentucky. |

| 151,428 | HART CO. | WOODSONVILLE | 01/29/2009 | 2,220 | Flood | 0 | 0 | 5,000 | 5000 | Ice melt from a recent ice storm coupled with heavy rain created minor flooding along the Green River near Munfordville. The river crested at 32.73 feet, 4.73 feet above flood stage, on January 30th at 1945 local time. | Melting from an ice storm on January 27th combined with rain on the 28th created minor river flooding along the Barren and Green Rivers in South Central Kentucky. Minor flooding was also reported on Stoner Creek in Bourbon County in the Bluegrass Region of North Central Kentucky. |

| 236,205 | HART CO. | ROWLETTS | 05/02/2010 | 643 | Flash Flood | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Kentucky 335 between the 2 and 3 mile markers was closed due to high water. | A stalled cold front over the Mississippi Valley spawned thunderstorms producing heavy rain from northern Mississippi through middle Tennessee and central Kentucky into southern Indiana. With little movement of the front, training of storms produced record or near-record 2-day rainfall totals from 8 to 10+ inches in many locations across central Kentucky. Major flooding occurred in at least 40 Kentucky counties, washing out roads and inundating municipal water treatment plants. Four lives were lost in Kentucky - three in vehicles and one in a home, where the resident was apparently electrocuted in high water. Over the following days, most area rivers were in flood, including some flooding along the main stem of the Ohio River. |

| 234,741 | HART CO. | HINESDALE | 05/02/2010 | 1,350 | Flood | 0 | 0 | 0 | 50000 | The Green River at Munfordville crested at 51.9 feet around 5 AM EST on May 4. Flood stage at Munfordville is 28 feet. Moderate flooding occurs at this level, with the city park below the U.S. 31W bridge flooded, and most agricultural bottom land flooded. | A stalled cold front over the Mississippi Valley spawned thunderstorms producing heavy rain from northern Mississippi through middle Tennessee and central Kentucky into southern Indiana. With little movement of the front, training of storms produced record or near-record 2-day rainfall totals from 8 to 10+ inches in many locations across central Kentucky. Major flooding occurred in at least 40 Kentucky counties, washing out roads and inundating municipal water treatment plants. Four lives were lost in Kentucky - three in vehicles and one in a home, where the resident was apparently electrocuted in high water. Over the following days, most area rivers were in flood, including some flooding along the main stem of the Ohio River. |

| 295,546 | HART CO. | WOODSONVILLE | 04/12/2011 | 1,545 | Flood | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | The Green River at Munfordville crested around 34.6 feet at 5 PM CST on April 13. Flood stage at Munfordville is 28 feet. Minor flooding occurs at this level with the city park covered by water. | A cold front brought heavy rains to the area, causing river flooding over much of south central Indiana and central Kentucky. Additional heavy rains later in April kept the Ohio River at Tell City above flood stage through the end of the month. |

| 304,751 | HART CO. | KESSINGER | 04/24/2011 | 1,735 | Flood | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | A spotter reported about 6 to 7 inches of water on roads in Western Hart county due to runoff. | Multiple episodes of severe weather affected the region on April 24. During the morning storms moved in from the south producing a couple of damaging wind gusts. Later in the afternoon the atmosphere became unstable once again with some dry air intruding at the mid levels. The strongest storms during the afternoon hours produced marginally severe hail. In addition, more storms training along the stalled boundary along the Ohio River exacerbated ongoing flooding and flash flooding. |

| 315,510 | HART CO. | WOODSONVILLE | 05/04/2011 | 420 | Flood | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | The Green River at Munfordville crested around 29.6 feet at 345 PM CST on May 4. Flood stage at Munfordville is 28 feet. Minor flooding occurs at this level, with the city park under the US 31W bridge flooded. | Area streams were running at high levels after flooding in April. A slow moving frontal boundary set off more heavy rains on May 2nd and 3rd. This caused renewed flooding on area streams. |

| 351,322 | HART CO. | WOODSONVILLE | 11/29/2011 | 540 | Flood | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | The Green River in Munfordville flooded due to heavy rain over the previous several days. The river crested at 30.66 feet. Flood stage is 28 feet. | On Saturday, November 26th, a deep full latitude trough across the Central Plains slowly moved east toward the Lower Ohio Valley. Light to moderate rain begin across central Kentucky around midnight Sunday morning and continued without interruption through late Monday as the southern portion of the trough developed into a closed low over the Tennessee Valley. Over a 36- to 45-hour period, 2 to locally as much as 4.5 of rain fell over all of central Kentucky. The greatest rainfall totals occurred within a broad band stretching from the Lake Cumberland Region northwest through Louisville into southwestern Indiana. Widespread minor flooding of fields and streams developed in Kentucky, with the closings of numerous low water crossings. Several larger rivers such as the Green, Rolling Fork and the Rough experienced minor flooding. |

| 462,390 | HART CO. | WOODSONVILLE | 07/06/2013 | 2,025 | Flood | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Heavy rains from the 4th through the 6th of July led to minor flooding on the Green River at Munfordville. Flood stage is 28 feet. The river crested at 31.8 feet during the early evening of July 7th. | An anomalous upper air pattern developed July 3rd as a deep trough over the Lower Ohio Valley became cutoff and essentially retrograded westward over the lower Missouri Valley. As this trough moved westward, southerly flow between it and strong high pressure off the mid-Atlantic seaboard brought tropical moisture northward across the Tennessee and Lower Ohio Valleys. Despite widespread cloudiness and cool temperatures, repeated tropical showers from July 4th through the 6th brought several episodes of localized flash flooding across the Commonwealth. Some river flooding developed during subsequent days on the Rolling Fork and Green Rivers. |

| 499,336 | HART CO. | HAMMONVILLE | 04/03/2014 | 1,637 | Flood | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | An employee reported around one foot of water over Hammonsville Road near Laton-Turner road due to an overflowing creek. | Repeated rounds of thunderstorms just north of a stalled boundary across central Kentucky brought excessive rainfall and flash flooding to many areas north and east of Louisville, including Oldham, Trimble and Henry Counties. Storms during the day on April 3rd brought around one inch of rain to many locations along and north of Interstate 64. During the late evening hours on the 3rd through early morning on the 4th, repeated storms brought another quick 2 to 3 inches, bringing 36 hour totals to over 4 inches, resulting in flash flooding during the early morning hours on April 4th. ||In addition to flooding, two elevated supercells developed April 3rd during the late afternoon and early evening hours along a boundary draped across central Kentucky. One of these storms brought golf-ball sized hail to Grayson County. |

| 562,175 | HART CO. | WOODSONVILLE | 03/05/2015 | 440 | Flood | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Several inches of snow followed by 1 to 2 inches of rain resulted in the Green River at Munfordville to rise above flood stage. The river crested at 32.49 feet during the early morning hours of March 6th and then fell below flood stage late on March 6th. | An intense storm system brought flooding rains to central Kentucky, followed quickly by exceptionally heavy snow. This amount of rain, followed by such heavy snow, is practically unprecedented. The upper level pattern featured a positively tilted upper trough across the desert southwest on the 3nd of March. A tight baroclinic zone stretched northeastward through southern Indiana. Strong southwesterly flow at lower levels brought rich moisture along this nearly stationary boundary. Initially, during the evening hours on the 3nd, rain developed along this boundary and gradually overspread all of southern Indiana and central Kentucky. Steady rain continued through the late afternoon on the 4th. Two to almost 3 inches of rain fell across north central and central Kentucky before precipitation changed into snow during the late afternoon hours on the 4th. Minor areal flooding developed with several roads and low water crossings closed. ||Rain changed into heavy snow near the Ohio River around 5pm, with precipitation changeover slowly moving farther south during the evening, Rain finally changed over to snow near the Tennessee Border during the early morning hours. Intense frontogenesis and lift associated with the right rear quadrant of a powerful jet led to the development of several intense snow bands where snow fell at a rate of 2 inches per hour. One band developed from near Breckenridge County and stretched through Bullitt County and across the northern Bluegrass. Under this nearly stationary band, snow totals ranged from 15 to locally over 20 inches. One reliable snow report from near Radcliff, Kentucky measured 25 inches, which is one inch short of the all time Kentucky storm total snowfall record. Snow diminished from west to east during the mid-morning hours on the 5th. Snow totals across south central Kentucky, adjacent to Tennessee, ranged from 5 to 8 inches. |

| 564,413 | HART CO. | WOODSONVILLE | 04/14/2015 | 700 | Flood | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | County officials reported that several roads had water flowing across them. | After a very wet start to April 2015, another slow moving system brought widespread heavy rain to portions of central Kentucky. Widespread amounts of 2 to 4 inches fell across central and southern Kentucky. Isolated 5 inch amounts were reported. This rain fell on top of already saturated ground and swollen rivers, creeks and streams and as a result, many rivers went into flood for a period of time. |

| 569,500 | HART CO. | WOODSONVILLE | 04/15/2015 | 350 | Flood | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Approximately 3 inches of rain fell on top of saturated ground and brought the Green River at Munfordville into flood. The river crested at 32.08 feet on the evening of April 15th. | After a very wet start to April 2015, another slow moving system brought widespread heavy rain to portions of central Kentucky. Widespread amounts of 2 to 4 inches fell across central and southern Kentucky. Isolated 5 inch amounts were reported. This rain fell on top of already saturated ground and swollen rivers, creeks and streams and as a result, many rivers went into flood for a period of time. |

| 606,444 | HART CO. | WOODSONVILLE | 12/27/2015 | 2,000 | Flood | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Several heavy rain events in late December brought 3 to locally 6 inches of rain to the area. This resulted in minor flooding on the Green River at Munfordville. The river crested at 28.27 feet on December 27th. | Several weather systems impacted the lower Ohio Valley during the last 10 days of December. Rainfall totals varied from 3 to locally 7 inches across much of the river basin, which resulted in significant rises and minor floods on area rivers, streams and creeks. |

| 626,625 | HART CO. | UNO | 05/26/2016 | 1,410 | Flash Flood | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | The Hart County emergency manager reported state highway 218 was flooded east of Horse Cave. | A long lived line of thunderstorms tracked from Missouri through Illinois and Kentucky before stalling out across south-central Kentucky during the late afternoon hours on May 26. The humid air mass and slow moving storms brought excessive amounts of rainfall in a short time period. Flash flooding caused some roads to be closed along with some stranded cars. ||Multiple people visiting and touring Hidden River Cave in the Horse Cave community became trapped as water rushed into the cave system. Rescue teams were initially unable to reach the stranded people, but eventually all were safely removed from the cave system. Between 2 and 4 inches of rain fell in less than 90 minutes. |

| 626,626 | HART CO. | HORSE CAVE | 05/26/2016 | 1,411 | Flash Flood | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Broadcast meteorologists relayed reports of people trapped in the Hidden River Cave System. Initial reports indicated that search and rescue teams were dispatched. | A long lived line of thunderstorms tracked from Missouri through Illinois and Kentucky before stalling out across south-central Kentucky during the late afternoon hours on May 26. The humid air mass and slow moving storms brought excessive amounts of rainfall in a short time period. Flash flooding caused some roads to be closed along with some stranded cars. ||Multiple people visiting and touring Hidden River Cave in the Horse Cave community became trapped as water rushed into the cave system. Rescue teams were initially unable to reach the stranded people, but eventually all were safely removed from the cave system. Between 2 and 4 inches of rain fell in less than 90 minutes. |

| 687,774 | HART CO. | HORSE CAVE | 05/21/2017 | 1,656 | Flash Flood | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Local law enforcement reported that Kentucky Highway 218 was blocked by high water west of US 31W. | An extremely warm, moist, and unstable air mass resided over the lower Ohio Valley during the middle of May. As a series of strong weather systems passed through the region, rounds of strong to severe thunderstorms developed and tracked across central Kentucky. |

| 711,489 | HART CO. | HORSE CAVE | 09/01/2017 | 615 | Flash Flood | 0 | 0 | 10,000 | 0 | The Hart County Emergency Manager reported that a water rescue was performed in Horse Cave after a vehicle stalled out in flood waters. | Powerful and slow moving Hurricane Harvey made landfall along the Texas Gulf Coast as a Category 4 hurricane. After the storm stalled along the coast, producing extreme and unprecedented amounts of rainfall along the Texas and Louisiana coasts that resulted in catastrophic flooding in the Houston metro area. The system then lifted toward the Tennessee and lower Ohio River Valleys on Friday September 1. Heavy rain spread across central Kentucky with amounts ranging from 4 to 6 inches. There were localized amounts of 7 to 8 inches across Warren, Barren, Allen, Simpson, and Logan counties. Many roads became flooded with high water and there were reports of high water rescues performed. |

| 800,092 | HART CO. | HAMMONVILLE | 02/20/2019 | 630 | Flood | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Kentucky 2785 was closed due to high water between mile markers 2.5 and 2.6. | On February 19, 2019, a broad upper trough dipped south to the Gulf of Mexico and carried abundant amounts of moisture towards the Ohio Valley. Once the moisture was transport was underway, isentropic lift caused 1.5 to 3 of rainfall along the Mississippi and Ohio River Valleys. The higher amounts went as far north as south central Indiana.||On the 20th, an upper trough axis and cold front pushed through southern Indiana and central Kentucky. The heaviest rain fell during the morning and into the afternoon hours before tapering off from west to east late on the 20th.||Moving into the 22nd, the upper flow amplified once again with a deep southwest flow aloft. Isentropic lift was underway resulting in widespread light rain pushing northward from Tennessee into Kentucky during the day. By that night, the ridge increased slightly across the region with a surface warm front pushing northward. More moderate to heavy rainfall fell during the night which caused localized flooding. ||On the evening of the 23rd, surface low pressure in the vicinity of the Kansas City, MO area with an arcing cold front pushed towards the Mississippi River. This cold front pushed through the region during the night and brought more moderate to heavy |rain along with some thunderstorms. ||All this rain and the saturated ground caused many flooding problems around central Kentucky. |

| 800,063 | HART CO. | PERRYVILLE | 02/23/2019 | 1,758 | Flash Flood | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Water was rushing over Lawler Bend Road. There was another road closed on KY 1140. | On February 19, 2019, a broad upper trough dipped south to the Gulf of Mexico and carried abundant amounts of moisture towards the Ohio Valley. Once the moisture was transport was underway, isentropic lift caused 1.5 to 3 of rainfall along the Mississippi and Ohio River Valleys. The higher amounts went as far north as south central Indiana.||On the 20th, an upper trough axis and cold front pushed through southern Indiana and central Kentucky. The heaviest rain fell during the morning and into the afternoon hours before tapering off from west to east late on the 20th.||Moving into the 22nd, the upper flow amplified once again with a deep southwest flow aloft. Isentropic lift was underway resulting in widespread light rain pushing northward from Tennessee into Kentucky during the day. By that night, the ridge increased slightly across the region with a surface warm front pushing northward. More moderate to heavy rainfall fell during the night which caused localized flooding. ||On the evening of the 23rd, surface low pressure in the vicinity of the Kansas City, MO area with an arcing cold front pushed towards the Mississippi River. This cold front pushed through the region during the night and brought more moderate to heavy |rain along with some thunderstorms. ||All this rain and the saturated ground caused many flooding problems around central Kentucky. |

| 883,151 | HART CO. | BONNIEVILLE | 03/12/2020 | 1,713 | Flash Flood | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Running water was flowing over the CSX railroad tracks. | On March 12th, two warm fronts moved north through the Ohio Valley carrying warm moist air ahead of cold front that moved through later in the day. As the cold front moved through, it produces heavy rainfall and flooding across central Kentucky. Severe hail and severe wind storms were also observed. |

| 913,761 | HART CO. | HIGH HICKORY | 07/17/2020 | 1,351 | Flash Flood | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Water was receding but still covering several roads just south of the Larue County line near US 31 East. | Upper high pressure was parked over the southern half of the United States while a slow moving front moved through Kentucky. As warm moist air advected northward, areas of heavy rainfall along the front caused flooding in two Kentucky counties. |

| 945,153 | HART CO. | WOODSONVILLE | 02/28/2021 | 1,131 | Flood | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | There was a water rescue on West Back Street. | A stalled frontal boundary brought waves of heavy rainfall to central Kentucky from February 26 through February 28. This caused record rainfall, isolated severe winds, and even a tornado. As a result, Bowling Green set a February daily rainfall record with 5.11 on the 28th. The severe winds brought down some trees and a power pole, but the most property damage came from a brief EF1 tornado. |

| 945,155 | HART CO. | HORSE CAVE | 02/28/2021 | 1,132 | Flood | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | There was flooding near the intersection of Highway 218 and 31 West. | A stalled frontal boundary brought waves of heavy rainfall to central Kentucky from February 26 through February 28. This caused record rainfall, isolated severe winds, and even a tornado. As a result, Bowling Green set a February daily rainfall record with 5.11 on the 28th. The severe winds brought down some trees and a power pole, but the most property damage came from a brief EF1 tornado. |

| 945,084 | HART CO. | HORSE CAVE | 02/28/2021 | 1,647 | Flash Flood | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Highway 218 in Horse Cave became impassable due to flooding. | A stalled frontal boundary brought waves of heavy rainfall to central Kentucky from February 26 through February 28. This caused record rainfall, isolated severe winds, and even a tornado. As a result, Bowling Green set a February daily rainfall record with 5.11 on the 28th. The severe winds brought down some trees and a power pole, but the most property damage came from a brief EF1 tornado. |

| 945,087 | HART CO. | LEGRAND | 02/28/2021 | 1,709 | Flash Flood | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | The 700-800 block and 40-50 block of Hundred Acre Pond Road was closed due to flooding. | A stalled frontal boundary brought waves of heavy rainfall to central Kentucky from February 26 through February 28. This caused record rainfall, isolated severe winds, and even a tornado. As a result, Bowling Green set a February daily rainfall record with 5.11 on the 28th. The severe winds brought down some trees and a power pole, but the most property damage came from a brief EF1 tornado. |

| 1,082,518 | HART CO. | PRICEVILLE | 02/16/2023 | 13 | Flash Flood | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.00K | Raider Hollow Road had to be closed due to flooding. | A strong storm system moved through the Ohio Valley beginning late in the evening on February 15th and continuing through much of the day on February 16th. An amplified mid- and upper-level trough moved across the central Plains during this time period, with an associated surface disturbance transiting from the Red River Valley northeastward into the Ohio Valley. A surface warm front was located parallel to the Ohio River during the majority of the event, with large-scale moist upglide persisting across much of Kentucky and southern Indiana. During the initial northward surge of moisture early on the 16th, elevated instability was sufficient for an isolated severe storm to develop across southern Kentucky, producing quarter-sized hail in Monroe County. However, through much of the remainder of the event, flooding would be the primary hazard as convection grew upscale into widespread disorganized clusters of moderate to heavy rain with embedded thunderstorms. |

| 1,206,923 | HART CO. | PRICEVILLE | 07/30/2024 | 13 | Flash Flood | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.00K | A vehicle had to be rescued along Raider Hollow Road. The vehicle was not on the road at the time of the rescue, but had fallen into a water-filled ditch along the side of the road. | A stationary front was located over the lower Ohio Valley from July 30th into July 31st, with upper level flow oriented from northwest to southeast across the region. This upper flow pattern brought multiple waves of showers and thunderstorms across southern Indiana and central Kentucky over this two day stretch. Scattered strong to severe storms mainly produced wind damage, with localized flash flooding also being reported where there was training of multiple rounds of showers and storms. |

| 1,236,440 | HART CO. | BONNIEVILLE | 02/15/2025 | 21 | Flash Flood | 2 | 0 | 10 | 0.00K | A woman called 911 after attempting to cross a flooded bridge AT 1900 Campground Road and water began to enter the vehicle. When the Bonnieville Fire Department arrived, they noticed a car partially submerged in high water. They noticed and extradited the driver's daughter from the car, but due to rising water couldn't get extradite the driver until the next day. Both occupants drowned. | A strong storm system moved across the Ohio and Tennessee Valleys on February 15th and 16th, 2025, bringing heavy rainfall and flooding, severe weather, and winter weather to central Kentucky. The large scale upper level pattern featured deep troughing ejecting across the central CONUS, with broad southwesterly flow occurring in the low and mid troposphere. Southerly flow helped to draw rich moisture up from the Gulf of America, with unseasonably high precipitable water for the middle of February, generally between 1.1 and 1.3 inches, overspreading the Tennessee and Kentucky. A nearly stationary surface front extending from west to east across the lower Ohio Valley provided a source for lift as warm and humid air ascended over a cool near surface layer. Light to moderate rain developed across the region early on the morning of the 15th, with rainfall getting heavier across south central Kentucky by around daybreak. This resulted in instances of flash flooding occurring across south central Kentucky during the mid-to-late morning hours. As the main surface low pressure system approached from the southwest during the afternoon on the 15th, the quasi-stationary surface front lifted into north central Kentucky, bringing a brief reprieve from rain across southern Kentucky while rainfall increased across northern Kentucky. As a broken line of storms developed ahead of an approaching cold front, temperatures and dewpoint temperatures increased considerably across southern Kentucky. This allowed for enough instability for a few strong to severe storms to develop near the Tennessee border. One portion of the line of storms produced a brief tornado over Simpson County, while other reports of wind damage and hail were received from Warren, Logan, and Monroe County. Still, heavy rainfall was the predominant impact from this system, as numerous instances of flooding and flash flooding were observed across Kentucky, and river flooding would occur over the following week. February 17th, one person drove into flood water and drown in Ohio County. Precipitation ended as a band of light to moderate snow on the morning of the 16th, producing accumulations of 1 to 3 inches before ending. |

| 1,258,969 | HART CO. | DEFRIES | 04/05/2025 | 17 | Flash Flood | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.00K | State Road 566 was closed near the Green/Hart County line due to high water. | On the night of April 2nd, 2025, a cold front approached the lower Ohio Valley. Along and ahead of the cold front, numerous supercells developed over southern Illinois and western Kentucky. These storms tracked eastward and occasionally grew upscale into a QLCS with bowing segments. Storms lasted all night and into the morning hours, as the cold front began to stall over the lower Ohio Valley. These storms left behind a wake of damage in many counties in central Kentucky. Over the next few days, waves of showers and storms rode along the cold front bringing lots of rain which lead to widespread flash and areal flooding. Showers and storms came through daily, until the evening of April 6th. Later, this flooding turned into historic and near-record breaking river flooding along many river basins. |

Probability of Future Events

Flooding in Hart County is a high-probability hazard, driven by frequent heavy-rainfall events, the county’s extensive river and stream network, and its karst landscape. Historical records indicate multiple flood or flash-flood events annually, with storm frequency increasing during spring and early summer when convective systems are most active. The Green River and Nolin River corridors experience periodic high water during multi-day rain events, while smaller tributaries—such as Bacon Creek, Lynn Camp Creek, Bear Creek, and Lick Creek—respond quickly to intense rainfall, creating short-notice flash-flood conditions.

Localized flooding is also common in karst areas, where sinkholes or drainage inlets can clog, leading to temporary ponding even outside mapped Special Flood Hazard Areas (SFHAs). Climate projections suggesting more frequent high-intensity rainfall events—particularly storms producing one inch or more of rain in a short period—may modestly increase flood probability over coming decades. For planning purposes, Hart County should expect recurring annual flood impacts, with several events capable of disrupting transportation or affecting structures each year and more significant riverine or flash-flood events occurring every few years.

Impact

Extreme heat can lead to heat exhaustion and heatstroke, particularly in outdoor workers, the elderly, and low-income households without access to cooling. It also increases energy demand, raising utility costs and the likelihood of power outages. Severe cold poses risks of frostbite, hypothermia, and infrastructure damage, including frozen pipes and malfunctioning heating systems. Both extremes can disrupt agricultural yields, livestock health, and local economies.

Built Environment:

Flooding can cause structural damage to both residential and commercial buildings and destroy furnishing and inventory.

Flooding will causes inconvenience or stoppage to many system. Transportation systems such as roads and railways become unpassable. Large amounts of water from a flood can affect water management systems such as the backup or hiatus of drainage, sanitary, and sewer systems. As heavy rains persist during a flood event, excess water drains into the ground water system. This causes the water table to rise and cause further ground water floods. If chemicals are mixed with flood waters, this can contaminate the ground water, a common source of fresh water for communities.

Natural Environment:

As flood waters engulf the surrounding natural environment, they are saturated with chemicals and other substances associated with the manmade environment that they have also been in contact with. As these abnormal waters settle and flows through natural ecosystems they can alter and even destroy both plant and animal life. When the flow of flood waters becomes so immense, it can physically destroy or uproot naturally growing vegetation and also drive specific species of animals out of their natural habitats for good.

Social Environment:

People

People with property located in the floodplain or within areas subject to seepage are vulnerable to flooding. Stoppage to transportation systems can make it very difficult for isolated populations to receive aid or escape breeching flood waters. Vulnerable populations, such as the elderly or people who need medical attention, may be temporarily cut off from accessing life-saving resources.

Economy

Floods can affect local economies by disrupting transportation systems needed for people to get to and from work and destroying places of business and means of production. When flooding occurs in more rural areas, livestock and agricultural system will be affected. Crops can be destroyed in the growing season, or prevent from seeding in the off season. Large insurance payouts to residents or business owners who have procured flood insurance might also have an economic impact.

Climate Impacts on Flooding:

Climate change models predict and increase in overall temperature globally for the coming decades, including the BRADD region. With a potential rise of several degrees Fahrenheit, multiple services, systems, and activities face disruption and impact. Temperature increases this small may not seem threatening, but the cumulative impacts will affect weather events, human health, and ecosystem functions, along with economic and social issues related to energy use and cost of living.

Working with

AT&T’s Climate Resilient Communities Program and the

Climate Risk and Resilience (ClimRR) Portal, BRADD identified additional opportunities for hazard mitigation action items associated with climate impacts for flooding in the Barren River Region. To view an interactive report of these findings,

click here.

Hart County’s vulnerability to flooding is moderate to high, shaped by its river corridors, steep drainage basins, low-water crossings, and karst topography. Communities located near the Green River and Nolin River, as well as structures and farms located along major tributaries, face increased exposure to inundation during prolonged rainfall. Rural areas with limited drainage infrastructure, older culverts, or undersized road crossings are particularly susceptible to washouts and access disruptions.

While the number of FEMA-classified repetitive-loss structures is low, many homes—especially older residences and manufactured housing—remain sensitive to flooding due to limited elevation, low foundation heights, or proximity to drainage paths. Karst-dense areas add unique vulnerability: blocked sinkhole inlets or saturated soils can cause sudden, localized flooding that is unpredictable and difficult to map. Agricultural operations may also experience repeated impacts when fields, fences, or access roads flood during storm seasons.

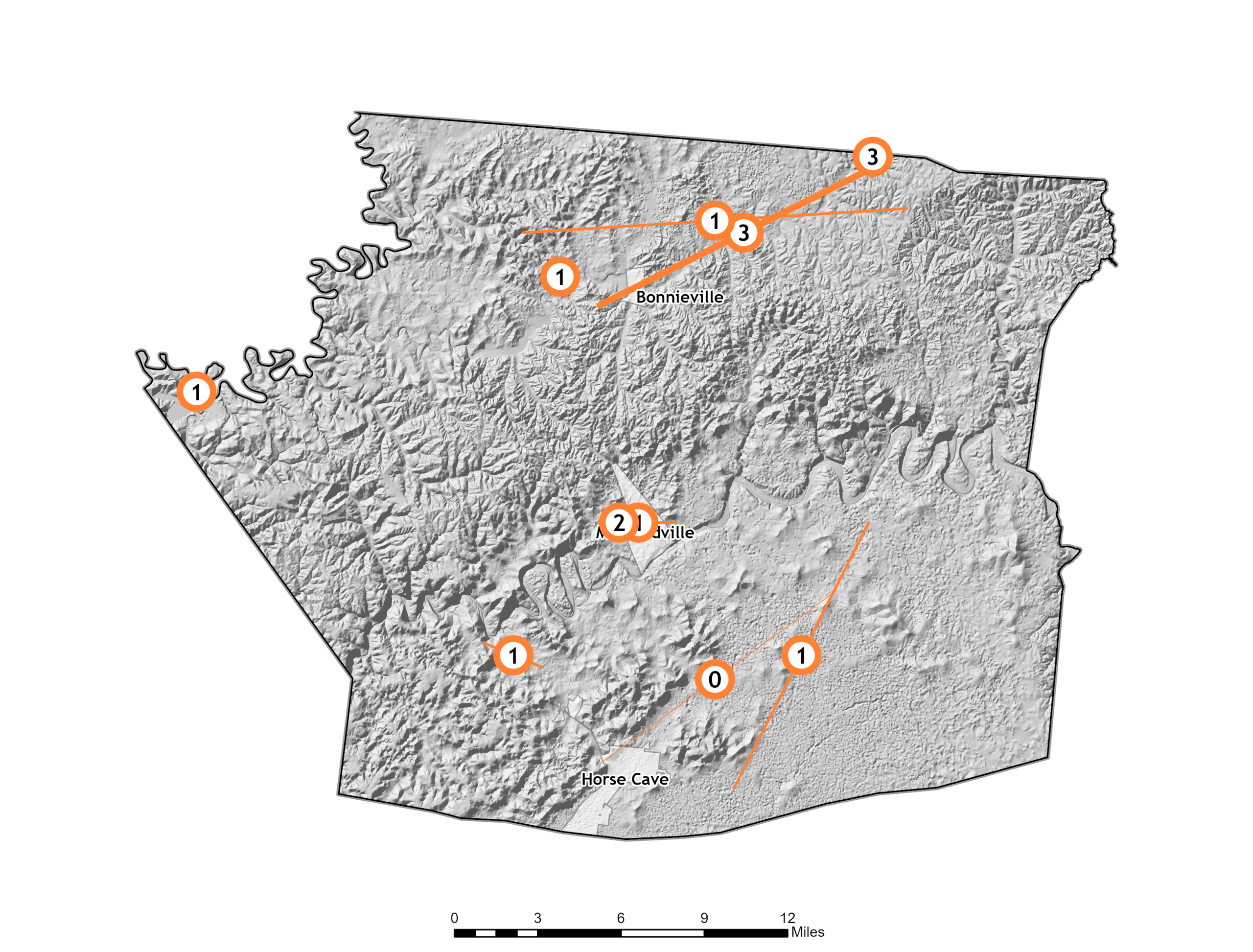

Populations most at risk include households with limited mobility, limited vehicle access, or medical dependencies, as well as residents living in low-lying rural areas where emergency response and evacuation are constrained by distance and narrow road networks. Critical facilities near stream corridors or in areas prone to access disruptions may face temporary operational challenges. Continued maintenance of drainage systems, improvements to road crossings, and public education on flood safety are key to reducing vulnerability across the county.